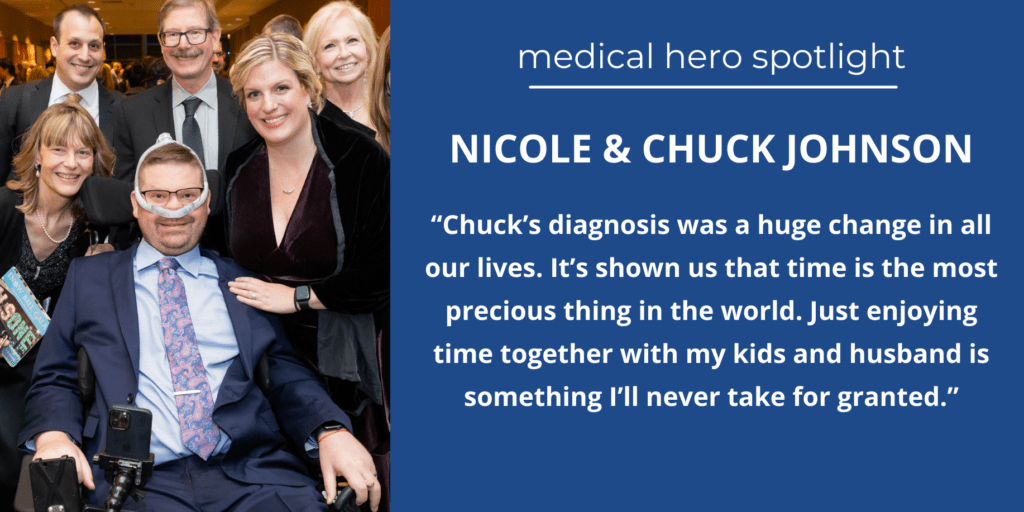

Chuck and Nicole Johnson were out celebrating her 37th birthday in June 2023, when Chuck mentioned his hands had been shaking during dinner. Nicole was somewhat concerned, but Chuck reassured her that it ran in his family and wasn’t anything serious.

Married for five years and parents to two toddlers, the couple was excited about expanding their family. Their hopes turned into joy when Nicole discovered she was pregnant that September. However, only a month later, Chuck began to realize that something was seriously wrong.

One morning, while singing “The Wheels on the Bus” with their two-year-old daughter, he struggled to lift her in the air—something that had never been difficult for the 6’5” former collegiate football player. This marked the beginning of a series of troubling health issues.

A Search for Answers

“I remember I had just finished a Teams call for work when he came into my office to talk,” Nicole recalled. “He told me he had lost 30 pounds since the summer without trying, felt weak, and was experiencing more frequent and noticeable muscle fasciculations.”

That moment set them on an intense diagnostic journey. Chuck couldn’t get an appointment with his primary care physician for several months, so they turned to a CVS MinuteClinic for initial bloodwork. The results showed abnormal liver enzymes. Concerned, Nicole urged Chuck to send the results to his doctor, who then found an earlier appointment for him. Further bloodwork led his doctor to suspect a liver issue, but that didn’t explain the muscle fasciculations. Eventually, the Johnsons were referred to a neurologist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. After an evaluation, the general neurologist suspected Chuck was in the early stages of ALS, though more testing was needed for confirmation.

Through the holiday season and into the new year, Chuck endured eight weeks of extensive testing to rule out other conditions with a neuromuscular specialist. On February 14, 2024, he was officially diagnosed with limb-onset, sporadic ALS.

From that moment, Chuck and Nicole’s daily lives changed drastically as they adjusted to his evolving health and treatment needs.

A Life-Altering Diagnosis

The next six months brought immense changes and challenges. In the final months of her pregnancy, Nicole juggled processing Chuck’s diagnosis, scheduling his care and treatments, acquiring necessary medical equipment, working full-time, coordinating childcare for their two kids, and preparing for their newest arrival.

“It was overwhelming,” Nicole admitted. “I barely had time to stop and process everything—there was just so much to do.”

Hope for treatment was quickly met with roadblocks. Chuck was immediately given the standard of care treatment approved for ALS, but the Johnsons had also started looking into innovative clinical trials. The HEALEY ALS Platform trial at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) where Chuck was receiving care, had already reached enrollment capacity. Other local trials were unavailable due to Chuck’s elevated liver enzymes. The couple considered traveling for other trial opportunities, but with Nicole’s pregnancy, it wasn’t a feasible option.

In May, they welcomed their youngest daughter, Jenna, into the family. By that time, Chuck was using a motorized chair, and his health continued to decline. His breathing difficulties eventually led to a stay in the ICU at the end of the summer, and his lung capacity dropped below the threshold for any clinical trial eligibility.

“Unfortunately, this situation is common for those with a fast-progressing disease,” Nicole shares. “Many people become ineligible for traditional clinical trials, and it can cause families to feel hopeless.”

However, in October 2024, Chuck was granted access to an investigational drug through the Expanded Access Program. Unlike standard clinical trials where participants may receive a placebo, this program ensured he received the actual treatment. Though not a cure, the oral medication is helping to slow the decline of his ability to speak and eat, providing more stability for the family in the short-term.

Finding Community Support

Since Chuck’s diagnosis, the Johnson family have relied on their network of friends, family, healthcare aids, and their community to provide the support needed to manage each day. The family has hired a caregiver who is with them full-time, as well as an au pair from Colombia who joined them this past year to help with any childcare needs. There’s nearly always another member of the family staying over the house as well to help with preschool drop-off/pick-up so Nicole can get some sleep.

For Nicole, coordinating the different care needed for her family involves a lot of planning.

“Sometimes I feel like a cruise director or the family CEO, with the level of project management that goes into planning our lives,” she laughs. “Luckily, organization is one of my strong suits.”

The Johnsons have also found community and support from local advocacy groups. Organizations like the Pete Frates Foundation, ALS One, and Compassionate Care ALS have offered grants, equipment, and emotional support. These groups have provided essential resources like a shower chair and Hoyer transfer lift, as well as opportunities for the family to participate in community events, raising awareness and funds for ALS research.

Nicole and Chuck have also become actively involved in advocacy, sharing their story at events like the ALS One Snowball gala in March 2025.

Treasuring Every Moment

Today, Chuck remains a dedicated father to his three children, despite his challenging journey with ALS. The kids love spending quality time with their dad by riding on his wheelchair, helping to feed him Oreos (while sneaking some for themselves), finding ramps in public places for him to use, and taking fun trips in the family’s new wheelchair accessible van.

“This was a huge change in all our lives, but they’ve adapted so well. It’s really showed Chuck and I that time is the most precious thing in the world, worth more than any material things,” Nicole says. “Just enjoying time together with my kids and husband is something I’ll never take for granted.”

To keep up with updates from the Johnson family, visit their website: https://makewayforchucklings.com/

To search for medical conditions in a specific location, visit our Search Clinical Trials page.

To stay informed about clinical trials, visit our Resources page.

Written by Lindsey Elliott, Marketing & Communications Manager, CISCRP | lelliott@ciscrp.org

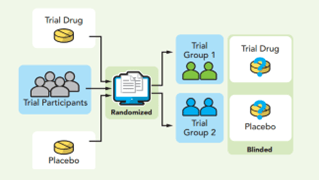

If you asked a member of the public to pick the first word that comes to mind when they think “clinical research,” there’s a good chance they would say placebo. And then if you asked them to define it, they may say something like, “It’s just a sugar pill.” Since there’s a

If you asked a member of the public to pick the first word that comes to mind when they think “clinical research,” there’s a good chance they would say placebo. And then if you asked them to define it, they may say something like, “It’s just a sugar pill.” Since there’s a

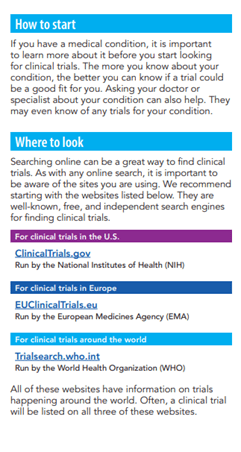

We have lots of information about clinical research participation, including helping to decide if participation is right for you (see our brochure,

We have lots of information about clinical research participation, including helping to decide if participation is right for you (see our brochure,

It is Monday morning at the CISCRP office, and I open my computer a few minutes before 9 AM and prepare myself for a new week. I normally work from home on Mondays, but a few colleagues who also often work from home were planning to come into the office in downtown Boston today, and I wanted to join them.

It is Monday morning at the CISCRP office, and I open my computer a few minutes before 9 AM and prepare myself for a new week. I normally work from home on Mondays, but a few colleagues who also often work from home were planning to come into the office in downtown Boston today, and I wanted to join them.